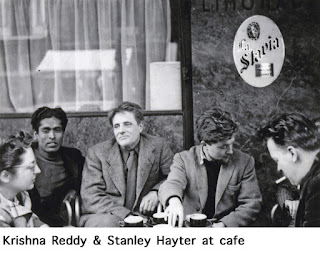

On August 22, 2018 one of the giants of twentieth century printmaking passed away at the age of 93. N. Krishna Reddy was instrumental in making printmaking something unique, not merely a secondary medium for creating a reproduction of an artwork in another form, as it had been perceived for much of the fifteenth through nineteenth centuries. He and his mentor, Stanley William Hayter, are far from common household names, yet their impact on Modernism proved fruitful in shaping the processes and works of some of the key figures of midcentury Modernism, such as Joan Miro, Louise Nevelson, Pablo Picasso, and Jackson Pollock.

Reddy was born in a small town in India in 1925. He went to university in his home country and began teaching art there in the 1940s. At this point he was working primarily in sculpture and painting. After WWII, as Europe was beginning to rebuild, Reddy made his way west and first settled in London in 1949. There he studied sculpture with Henry Moore. By the next year he had moved on to Paris where he also studied sculpture with Ossip Zadkine.

Stanley Hayter had first set up his workshop (Atelier 17, but now running as Atelier Contrepoint) in the late 1920s. It was a meeting place for artists from around the world, who had come to Paris to study the evolving styles of early abstraction. Hayter’s workspace and press allowed these artists to try their hand at engraving and etching, even if their primary media were something other than printmaking. With the onset of WWII Hayter moved Atelier 17 to New York City for a period, but by the time Krishna Reddy was in Paris, Hayter had returned and was running both the American and French versions of the workshop for a period.

Reddy took to printmaking, especially engraving, right away. He shared Hayter’s enthusiasm for the direct processes of working a metal plate. Eventually, during the 1950s, Reddy was named as a co-director of Atelier 17 in Paris. It was not odd that an individual who had originally trained as a sculptor would become a director of the most significant printmaking workshop in the world. Hayter, himself, had started out as a painter and continued to paint throughout his life. Helen Phillips, Hayter’s second wife, was also primarily a sculptor before she met her husband and began working in etching and engraving processes. This was also the case for the American Shirley Witebsky, Krishna Reddy’s first wife. With this group of very physical printmakers it was no wonder that some new, experimental, and significant changes would soon be discovered at Atelier 17.

The most famous technique to come out of Atelier 17 is often called Color Viscosity Etching. It was usually called Simultaneous Color Intaglio printing by both Hayter and Reddy. The process was discovered somewhat accidentally by Reddy and his fellow countryman, Kaiko Moti, before being fully developed by Hayter and Reddy. At its root is the tendency for two oil-based inks to reject each other when one is oilier than the other. If an oilier ink is rolled onto the surface of a plate, another, tackier ink can be rolled over the first inking without disrupting that initial ink surface. This became most important when the sculptural aspects of Reddy’s (and others’) works allowed rollers of different densities to apply the inks. A hard roller would deposit an oily ink on the top surface of the etching plate, whereas a softer roller with a tackier ink could deposit ink on a lower surface, while not changing the ink from the previous roller. This discovery finally achieved the effect that Hayter had long been searching for—a way to ink an etching plate in colors so that it could be sent through the press only once.

The technique of simultaneous color printing became synonymous with the artists of Atelier 17. Hayter had his own ways of utilizing the process which changed over time, as he worked in the collaborative atmosphere of Atelier 17. Reddy, however, made the process his own. While Hayter favored engraving and the use of etching acids to develop textures and depth in his plates, Reddy was prone to work the plate in a more sculptural way. Using traditional hand engraving tools alongside electric rotary (aka Dremel) tools, Reddy produced what were essentially low relief sculptures in a metal plate. As aggressive as this method might sound, under his masterful hand, using the color viscosity method, Reddy was able to achieve incredibly nuanced inkings of his intaglio prints.

Floraison (or Blossoming) from 1965, was the first work that Reddy created entirely utilizing hand tools, without any etching techniques. It is reminiscent of many of his and Witebsky’s etchings of this period. The true print collector can relay just how interesting these works are to examine. They may look lovely framed, but are best enjoyed outside of a frame where the embossed depth of the plate can be seen on the back side of the sheet of paper. Close examination reveals that Reddy was a master of color with this technique. What first appears to be a basic inking with black and blue is discovered to be more complex. Reddy actually used a pale orange color with one of the rollers. This layer of color is made to mix with one of the lower layers of blue—instead of rejecting it—creating a richer gray than what is possible with an inking of black alone.

Hayter wrote two editions of his seminal work New Ways of Gravure that explain the process of Color Viscosity printing. They are each illustrated with works by a variety of artists—including Reddy—who passed through Atelier 17. However, Reddy’s book, Intaglio Simultaneous Color Printmaking: Significance of Materials and Processes, goes much further into the details of the process, revealing just how complex the inkings of some of his prints were. It is an essential handbook for anyone interested in learning the process.

One of the last major exhibitions to highlight Reddy’s work was at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City, about two years ago. I was fortunate to see Workshop and Legacy: Stanley William Hayter, Krishna Reddy, Zarina Hashmi at the Met in February 2017. This was not a huge exhibition, but the limited works actually made it a more intimate encounter with the works. There were several very important Hayter works on display (including two works that appear in my own collection) but there were many Reddy pieces that I had never seen in person. Also included was one of Reddy’s sculptures. This exhibition was the highlight of my trip to New York. It has been instrumental as I put together an exhibition of Atelier 17 artists from my own collection.

With the loss of Reddy, there is one remaining major figure from Atelier 17 still working. Hector Saunier continues on at the Atelier. He started at Atelier 17 after Reddy moved to the U.S. Luckily, with shows like the one at the Met, and others that have been touring (such as Syracuse University’s About Prints, named after Hayter’s other major publication), the important work of these artists is not being lost. A new generation can discover just how influential these men and women were on Modernism in its early days.

No comments:

Post a Comment